Sermon for 4th October 2020 – St Michael and All Angels (transferred from 29th September); St Francis of Assisi: Animal Welfare Sunday: on Zoom

Revelation 12:7-12; Luke 15:3-7 (see http://bible.oremus.org/?ql=468720899)

St Francis of Assisi (unknown artist), from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Francis-of-Assisi/images-videos, accessed 8th October 2020

Today we commemorate St Michael and All Angels, and St Francis and his love for animals.

Blessings of the animals and pet services are usually great fun, especially for the children – although perhaps a bit less so for their parents, who have to catch the hamsters, cats and other exotic creatures which escape from their baskets during the service. We don’t have that problem, because all our pets are with us at home and they are only appearing and being blessed, like us, on Zoom. But I still think that it is important that our beloved animals, our furry friends, should have the benefit of a blessing at least once a year. In saying Saint Francis’ prayer and in blessing the animals, as we’re going to do, we are giving thanks for all God’s work in creation.

But what about those angels? I am what is called a liberal theologian, which means (among other things) that I am not wedded to taking everything in the Bible absolutely literally. I think this passage about war breaking out in heaven and the battle between Michael and his angels and the Dragon, known as Satan and the Devil on other occasions, is a good case in point. I dare say if we were in the south of Italy, where they are more used to miracles, we would hear this lesson from the book of Revelation without batting an eyelid. We wouldn’t be too troubled about exactly where heaven was or what the Dragon really represented – or indeed possibly who the Devil was. But we do understand the contrast between good and evil and the way in which frequently, in order to uphold the right and the good, there has to be a battle.

‘Guido Reni’s resplendently theatrical depiction of St Michael, part Roman soldier, part ballet dancer, was painted in 1635 and can be seen in the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione in Rome.’ (Andrew Graham-Dixon at https://www.andrewgrahamdixon.com/archive/itp-238-st-michael-archangel-by-guido-reni.html, accessed 8th October 2020)

We will notice in passing that it is not George who slays the Dragon but Michael, although the stories are a bit similar. Also there is seemingly a second fight. It’s not just Michael. The good angels have conquered the serpent as well, the Dragon, ‘by the blood of the Lamb, by the word of their testimony and by their willingness to die’ for the cause.

So there are perhaps two stories here. One is the story of the war in heaven between Archangel Michael and the great dragon, a.k.a. Lucifer, the devil; and the other, where salvation is achieved and victory over evil by the blood of the lamb.

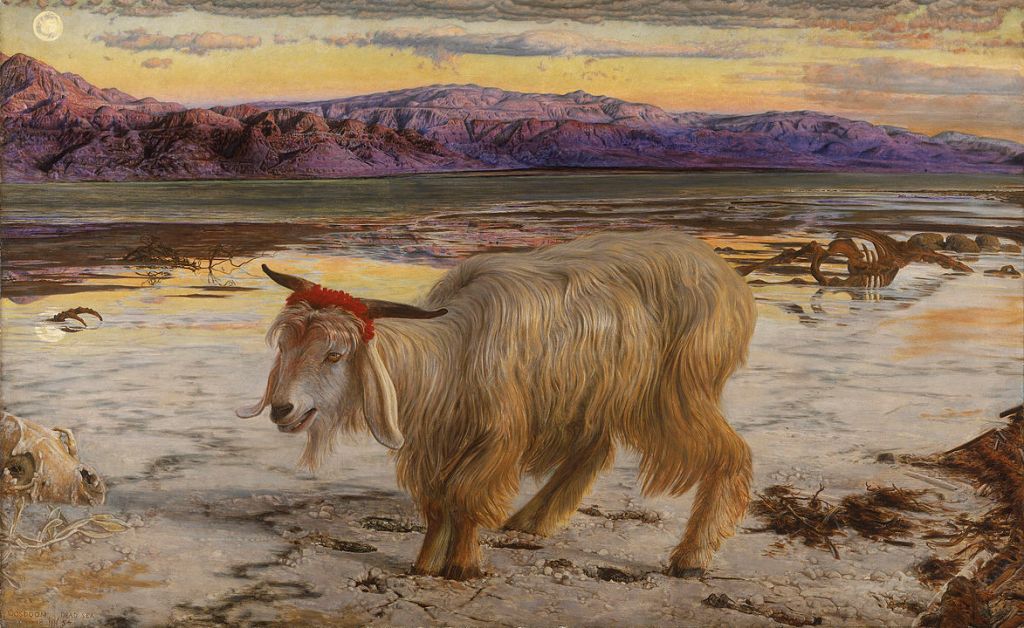

In Jewish tradition there is this idea of a scapegoat, which could also be a ‘scape-lamb’; you read in Leviticus chapter 16 how this is supposed to work sacramentally, where all the sins of the people are symbolically loaded on the back of a lamb or a goat which is then cast off into the desert. In a sacramental sense, the scapegoat ‘takes the burden’ of the people’s sins, and dies for those sins. You can say that the lamb died for the sake of the people’s sin. It is very similar to the idea of what Jesus has done, ‘dying for our sins’ on the cross.

The Scapegoat, by William Holman Hunt (1854-1856) in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight

Liberal theologians like me have difficulty with the idea that a loving God would have demanded a human sacrifice, but certainly we can follow the development of the idea of the ‘atonement’, as it is called, by Jesus on the cross, by looking at the Jewish tradition of the scapegoat.

You might think, from this story of the scapegoat, that people at the time of Jesus might not have been very nice to animals. But I don’t think we can necessarily draw that conclusion. There are many instances in the Bible where Jesus appears to love and care for animals. In the sermon on the Mount: ‘Behold the fowls of the air: they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them’ [Matt.6:26]; and as we can see in the parable of the lost sheep and indeed the other parable of the good Shepherd, Jesus certainly didn’t just think of lambs in the context of sacrifice, but rather as animals to love and care for.

And this is one of the things which produced Saint Francis of Assisi’s distinctive theology, his famous preaching to the animals and his love for all creation. ‘Brother Sun’ and ‘Brother Moon’, for instance. So on this feast of Saint Francis of Assisi it’s entirely right that we should bless the animals and bring them before the Lord in prayer. In a minute I will ask you to find your pets or pet pictures and put them up for a blessing.

But first, a final thought. This is the last of these Zoom Eucharists and we have become, I think, a proper little congregation. A proper little flock. Soon we will return to the various churches that we came from, as they are able to reopen for worship.

It seems to me that it would be nice to do something, to give some tangible expression to our gathering in the name of the Lord, every Sunday for the last few months. We could, of course, pass the plate round, and we would have to do it virtually using PayPal or something similar. But I think I’ve got a better idea.

It occurred to me that on the day when we are blessing the animals, we should try to help our various zoos – Regent’s Park, Whipsnade, Chester and Bristol (where I still hear Johnny Morris in my head) and all the others. They are all having a very hard time. Feeding all the animals at Regent’s Park, at London Zoo, for example, costs £1 million per month. So my suggestion is that, as we give thanks for creation and all the wonderful animals that the Lord has created, we should all consider taking a trip to the nearest zoo to where we are in the next week or two. I think that zoos are eminently safe places to visit even in the Covid epidemic, and the price of admission, if enough people turn up, will help to restore their finances. [Donations – https://tinyurl.com/y2m75jd4, https://www.chesterzoo.org/support-us/, https://bristolzoo.org.uk/save-wildlife/bristol-zoological-society-appeal, or to help a wonderful zoo in Hamburg, https://www.hagenbeck.de/de/_news/tierpark/Unterstuetzung_FAQ.php ]

We shouldn’t forget that the animals themselves will be very pleased to see us, because, as we ourselves have found, being locked down in quarantine with nobody to see is very lonely and no fun. I think that Jesus the Good Shepherd would want you to find out where your nearest zoo is and go and see all the lovely animals in it, very soon.

Blessing of the Animals

Now we are going to bless all animals. If you have any with you, or any pictures of animals whom you used to have, please do bring them into the picture.

Blessed are you, Lord God, maker of all living creatures.

You called forth fish in the sea, birds in the air and animals on the land.

You inspired Saint Francis to call all of them his brothers and sisters.

We ask you to bless all animals, and those which are or were our pets.

By the power of your love, enable them to live in peace and harmony.

May we always praise you for all your beauty in creation.

Blessed are you, Lord our God, in all your creatures!