Sermon for Evensong on the First Sunday in Lent, 9th March 2025

At St Peter’s Church, Old Cogan

Jonah 3

Luke 18:9-14

https://bible.oremus.org/?ql=608348962

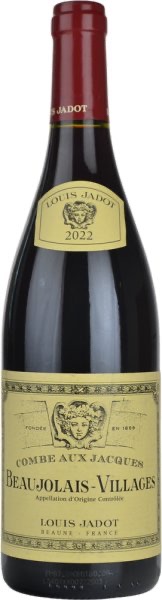

Last Wednesday, Ash Wednesday, I did some shopping in one of our local supermarkets. I accidentally walked down the aisle containing wine and beer, and stumbled across Beaujolais Villages from one of the finest Burgundy producers, rather curiously marked as ‘clearance’ – at less than half the normal price.

Now on the first day of Lent this was rather a challenge. Could I resist buying it at less than half price? On Ash Wednesday it was the start of Lent, and one of the things which one is supposed to do is to give things up, to fast. What was I supposed to do about this wonderful wine bargain?

At the same time I was starting to think about this service, and what I would say to you in my sermon. I looked at our Bible lessons prescribed for today, and came across the third chapter of the little book of Jonah.

A little like Louis Jadot’s fine Beaujolais, the passage chosen wasn’t quite what I had expected. That was nothing about the whale. If I asked you what you associate with the name of Jonah, I would be mighty impressed if the name ‘Nineveh’ was on your lips instead of something about a whale.

Our lesson today tells you about Jonah going and uttering a prophecy to the people of Nineveh who have been misbehaving in a sinful way, telling them that God had warned that they would come to a bad end if they did not mend their ways. The ruler of Nineveh told the people to put on sackcloth and ashes, to put on visible signs of repentance, and to turn back to the true God. But you have to know that this is Jonah’s second go at this task from God. The first time around, when God was telling him to give this bad news to the people of Nineveh, he ran away, bought a passage on the ship and then, as a result of the ship being caught in a storm, he drew the short straw and was chucked overboard so as to lighten the load on the ship and to save it from being overwhelmed by the waves. And he was eaten up by a whale.

At this point when I am talking about the book of Jonah, as an ancient maritime lawyer I always use the opportunity to mention this as an early instance of the legal doctrine of general average, an “extraordinary sacrifice made to preserve the safety of the ‘maritime adventure’”, as the Marine Insurance Act1906, which is still good law, puts it; although general average doesn’t involve chucking people over the side as opposed to cargo or the ship’s tackle, of course, or making a special payment for services to prevent the ship being lost. So I won’t mention that particularly here but rather we should concentrate on Jonah’s encounter with the whale.

I’m not sufficiently up on marine biology to be able to express a view on how plausible this is as a literal account, but I think it is fine as a colourful illustration of how God might intervene to persuade somebody who was a bit reluctant. Jonah having been spat out safely, as you are, if you’re eaten by a whale, after three days, he was indeed persuaded, and he went and undertook his task. He told the people of Nineveh how awful they were, how they needed to change their ways, to repent: a bit like what we are supposed to do in Lent, I suppose.

You can see why Jonah was reluctant. Being the bearer of bad news is never a popular thing to do, especially when you are speaking truth to power. It’s something we’ve noticed in recent days in the way in which our various leaders are not telling President Trump what time of day it is.

Not but what Jonah, no doubt emboldened by his whaling experience, did deliver his message to the people of Nineveh, and he received a reception which was entirely different from what he had feared. God had noticed the fact that the people of Nineveh had changed their ways, and he did not punish them.

So – what should we do? How should we change our ways in the 40 days leading up to Easter? What about fasting? Well, another thing to put into the mix is that we mustn’t crow about whatever it is that we do do; so if you are able to write a cheque for an eye-watering amount of money to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, say, or even, maybe, for the Penarth Ministry Area, such that you make that gift instead of treating yourself to a holiday in Gstaad for skiing, you mustn’t talk about it. You mustn’t crow about it. Think about the Pharisee and the publican. All you should do is to ask the Lord for forgiveness because you are a sinner. Whatever sins you have committed, you just say, quietly and privately, ‘Have mercy on me, a sinner.’

I guess that bears on how you should conduct yourself at charity auctions. Maybe you will have to appoint a proxy to bid for you next time you are minded to go and support Welsh Rugby at some appropriate dinner or other, but I leave that to your discretion.

What about that Beaujolais? Well I offer this as a true story which may or may not inspire you. I know that I am very bad at giving things up, but equally I’m not sure that my giving things up really has any benefit to anybody else except possibly me. But I am enormously comforted by a verse in Isaiah about fasting. Let me quote it to you.

‘Is not this the fast that I choose: to loosen the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?’ (Isaiah 58: 6,7)

Now I do think that that is more my kind of fast. So what I usually do – and I am going to do it this Lent – is, every time I eat out, (and that includes pies on the motorway), I will keep a note of what I spend; and at the end of Lent I will look at all those bills and work out what it would have cost to invite another person to join me each time: an absent guest, if you like. I will tot up the cost of the absent guests and I will give that to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Maybe that’s a sort of fast that you could undertake too.

Oh – and, yes, about the Beaujolais. I bought three.

Amen.

Hugh Bryant