A Sermon for Evensong at All Saints, Penarth, on the First Sunday of Easter, 16th April 2023

Lessons: https://bible.oremus.org/?ql=548333336

Daniel 6:1-23; Mark 15:46 – 16:8

This is the first Sunday in the 50 days from Easter to Whitsunday, Pentecost. So where are we now, one week on from Easter Sunday? Well, leaving aside for a minute the story of Daniel in the lions’ den, in our Bible readings, in the Lectionary, we are at the very end of Saint Mark’s gospel.

But before we start looking at that, you might wonder why our first lesson was the wonderful story of Daniel in the lions’ den, and you will, no doubt, be relying on me to pull out a suitable lion story.

Many people see lions in their mind’s eye as just bigger versions of ginger tomcats, and just as lovable. Just like the lion you can see on YouTube in a lovely little documentary which was made in the 1960s (https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLx1gRyewAnQZhBqiNNP-u9V9sUsi36ebK), about a couple of likely lads living in swinging London; in Chelsea, who acquired a lion cub from Harrod’s pet department. In those days the ‘well-known Knightsbridge corner store’ even had a pet department, where you could buy a lion cub.

And they christened him Christian, Christian the Lion, which was rather nice, and took him home to their flat. Once he’d settled in, they put him on a lead and took him for walks up and down the King’s Road, perhaps stopping to exchange the time of day with Mick Jagger as he stepped out of his elegant house on Cheyne Walk.

Christian the Lion stopped being a lovable cub and got rather too big to go out safely without the risk of his taking a leaf out of Hilaire Belloc’s book.

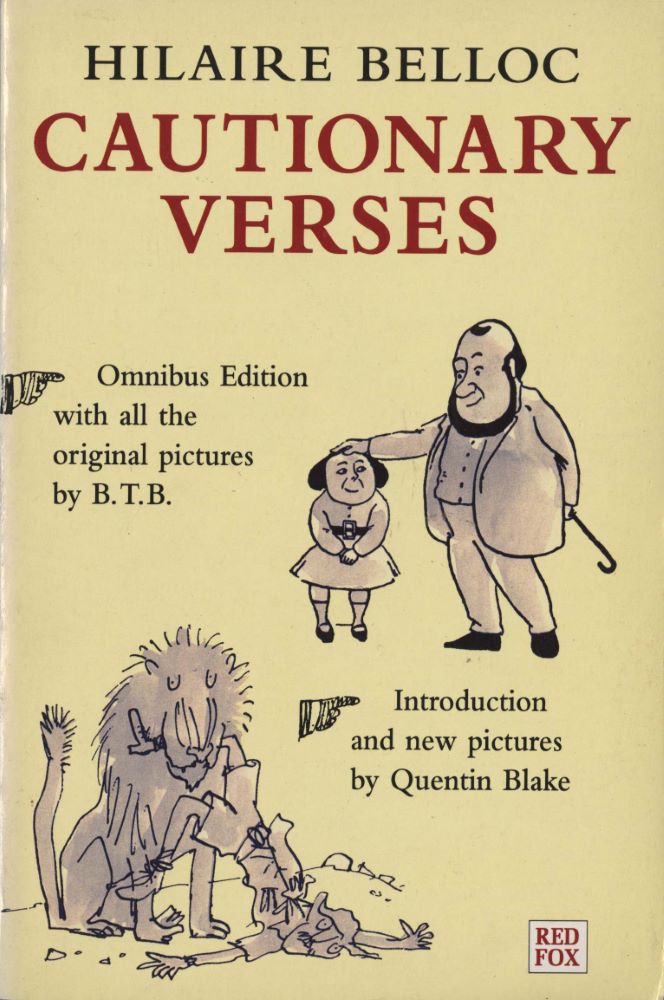

I am sure you will remember Hilaire Belloc’s ‘Cautionary Tale’ of Jim, who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion. Shall I read it to you?

There was a Boy whose name was Jim;

His Friends were very good to him.

They gave him Tea, and Cakes, and Jam,

And slices of delicious Ham,

And Chocolate with pink inside,

And little Tricycles to ride,

And read him Stories through and through,

And even took him to the Zoo-

But there it was the dreadful Fate

Befell him, which I now relate.

You know – at least you ought to know,

For I have often told you so-

That Children never are allowed

To leave their Nurses in a Crowd;

Now this was Jim’s especial Foible,

He ran away when he was able,

And on this inauspicious day

He slipped his hand and ran away!

He hadn’t gone a yard when – Bang!

With open Jaws, a Lion sprang,

And hungrily began to eat

The Boy: beginning at his feet.

Now just imagine how it feels

When first your toes and then your heels,

And then by gradual degrees,

Your shins and ankles, calves and knees,

Are slowly eaten, bit by bit.

No wonder Jim detested it!

No wonder that he shouted “HI!‟

The honest keeper heard his cry,

Though very fat he almost ran

To help the little gentleman.

“Ponto!” he ordered as he came

(For Ponto was the Lion’s name),

“Ponto!” he cried, with angry Frown.

“Let go, Sir! Down, Sir! Put it down!”

The Lion made a sudden Stop,

He let the Dainty Morsel drop,

And slunk reluctant to his cage,

Snarling with Disappointed Rage.

But when he bent him over Jim

The Honest Keeper’s eyes were dim.

The Lion having reached his head,

The Miserable Boy was dead.

When Nurse informed his parents, they

Were more Concerned than I can say:-

His Mother, as she dried her eyes,

Said, “Well- it gives me no surprise,

He would not do as he was told!”

His Father, who was self- controlled,

Bade all the children round

attend To James’ miserable end,

And always keep a hold of Nurse

For fear of finding something worse.

Hilaire Belloc (1907) Cautionary Tales,

included in Cautionary Verses, Omnibus Edition, (1993) London, Jonathan Cape

Thinking of Daniel’s escape from the den of lions, the story of Jim is a very good illustration of the fact that lions are not nice pussy cats; although in distinct contrast the story about Christian the lion does have a happy ending – perhaps I should issue a spoiler alert at this point.

The two chaps gave Christian to Joy Adamson of ‘Born Free’ fame for her to introduce the lion to the wild in Africa. A couple of years later they went to Kenya, and perhaps showing that touching faith in leonine good nature, which they had originally exhibited when they adopted Christian, they went for a walk in the bush in the hope of seeing lions, and, incredibly, a large male lion did appear, and he came bounding towards them. I think any normal people would have turned tail and fled; but not these two. They stood there, and this mighty king of the jungle leaped up and put his paws around their necks, licking them and embracing them. He was Christian, he remembered them, and he loved them.

Well, in the middle of all these nice lion stories, we mustn’t forget where we came in, which is, after all, one of the nicest lion stories, the one about Daniel in the den of lions. King Darius is tricked by jealous courtiers into having to condemn Daniel to what was normally a bloody fate, by being locked up in a den of lions overnight.

The great king Darius was terribly distressed. Should he uphold the law which he had made, his interdict, or should he spare Daniel who had become his most trusted administrator? And he decided he had to uphold the rule of law, the immutable law of the Medes and the Persians.

Poor Daniel had to be condemned. It was pretty ironic that Daniel had been condemned for worshipping the one true God, but the king figured that the only way Daniel could be saved was by praying to that same God, and indeed so he was, protected by an angel from being eaten by the lions.

But why do we remember Daniel at Easter? I think because, here again, after shutting somebody up in a place of death they rolled away the stone blocking the entrance and the dead man came out alive.

What about Jesus’ empty tomb? What happened to Daniel was nothing like as mysterious. Certainly if all you have to go on is Saint Mark’s gospel and this original so-called short ending, what happened is that the three ladies, the two Marys and Salome, found that the stone sealing the tomb had been rolled away and a young man in white was sitting inside, who told them that Jesus had been raised and that he was not there.

The young man was presumably an angel too; he had been promoted from lion-taming duties by this time, and he told the ladies to go and tell the disciples and Peter that Jesus was going ahead of them to Galilee where they would see him. And they fled in terror, and in fact told no one. The last words were, “…and they said nothing to anyone; for they were afraid”.

The original Greek words have intrigued scholars ever since. Literally it does not say, “for they were afraid”. It says, “they were afraid, for…” Or “they were afraid, because…”. It looks as though something is missing; but is that something all the material that’s in the other gospels, for instance about the two men in white and Mary hearing a familiar voice, thinking it was the gardener and and then recognising her teacher, and so on? Perhaps not. Then Mark would have made a gospel which really spoke to people like us, people who haven’t experienced the miracle of resurrection with their own eyes.

It is generally accepted that Mark is the earliest gospel, so this is the one which most closely reflects what the earliest Christians said about what happened on Easter morning. There is a lot more to come, when we do look at the other gospel accounts, in the weeks to come.

But I expect you’re not really sitting down and reading great tomes about it just now. One week on from a really happy Easter Sunday, as we come back to church today, it has still got a gently vague, happy buzz to it.

The Lord is risen; he is risen indeed! We’ve just sung ‘Jerusalem the Golden’, but perhaps in this Easter season we will also sing ‘Ye Choirs of new Jerusalem’, which has this splendid verse:

How Judah’s Lion burst his chains,

and crushed the serpent’s head;

and brought with him, from death’s domains,

the long-imprisoned dead.

The lion. The Lion of Judah. We haven’t even mentioned C.S. Lewis, and Aslan, the lion who stands for Jesus in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The Lord is risen. He is risen indeed.